Wondering What to Do with Your Life? Lessons From 12,000 Interviews on Finding a Fulfilling Career

What happens when three college friends have an "oh shit" moment about their futures and decide to interview 85 people across 18,000 miles? For Nathan Gebhard, it became a 22-year mission that's helped millions find their path and revealed uncomfortable truths about why most of us end up in careers we never really chose.

This is an edited version of my conversation with Nathan Gebhard, Co-Founder of RoadTrip Nation. If you want to watch the interview, you can find it on YouTube, and if you want to listen to it, you can access it on Spotify.

The "Oh Shit" Moment

Picture this: You're in college, surrounded by friends who seem to have it all figured out. One's pre-med because his whole family are doctors. Another's joining the family business. And you? You're planning to be a management consultant because... well, it sounds impressive at family barbecues.

Then reality hits.

"I think all three of us had this kind of 'oh shit' moment where we just realized the life we were living was not of our own making, not of our own design."

This is how Nathan Gebhard describes the wake-up call that would eventually become Road Trip Nation—a movement that's helped millions of people find their authentic career paths.

But let's back up. Because Nathan's story starts with something we can all relate to: that sinking feeling when you realize you're sleepwalking toward a future you never actually chose.

Nathan: When I went to college, I thought I was going to be a management consultant. And if I really, truly understood who I was and understood what management consulting was, I would realize the disconnect immediately. And I just never even was thoughtful enough about it. I literally hate wearing nice clothes. And so the idea of working in a job that would put me dressing up all the time was painful.

Sound familiar? How many of us drift toward careers that look good on paper but feel wrong in our gut?

Nathan's moment of clarity came during what should have been a routine informational interview. What happened next would change not just his life, but the lives of thousands of others searching for their own path.

The Lunch That Changed Everything

Sometimes the smallest conversations spark the biggest transformations. For Nathan, it was a lunch with a management consultant after a college career fair, a lunch that made him "totally freak out."

Nathan: At some point through college, I met a consultant, a management consultant, and took him out to lunch. And I totally freaked out after lunch. I was like, so tell me about travel and stuff. And this guy was super into travel. And he's like, "Oh, you can go here, you can go there and you go this. One day you're in the middle of the country, like consulting a tire company. And the next day you're up in New York City."

And I was like, "What if you want to just stay by the ocean?" And he was like, "Well, maybe like five, 10 years in when you build enough seniority, you can decide where you want to be located."

Two simple realizations hit Nathan like a freight train:

He'd have to move away from the ocean (his happy place)

Where he lived and worked wouldn't be up to him

Nathan: And this guy loved his job. So I don't know, he was in the exact perfect place. He loved dressing up. And he loved traveling everywhere. It just was totally incongruent with who I was as a person. And I never even thought about that until, I don't know, my third year in college, which is ridiculous.

The Power of One Simple Question

What emerged from Nathan's crisis was a deceptively simple idea: "Take somebody out to lunch who loves their work, ask them how they got there."

That one question would become the foundation of everything that followed.

Nathan: It just started as this simple little project of could we interview a bunch of people who love their work so that from their stories, we could write our own story.

I called the Supreme Court, the highest court in the States and asked for Sandra Day O'Connor, who's the first woman Supreme Court Justice from the 1-800 number on the Supreme Court website. Mike cold-called Saturday Night Live, the director of Saturday Night Live every three days for three months straight. And so we did these non-skilled, just hustle trying to get people to do our interviews.

We ended up leaving two weeks after September 11th, and we did a three-month road trip for 18,000 miles and interviewed 85 people. It was mind shifting, life altering.

KEY INSIGHT: Sometimes the most powerful career advice comes not from career counselors or online tests, but from simply asking people who love their work: "How did you get there?"Why We All Feel Lost: The System That Creates Confusion

Before we talk about what Nathan and his friends discovered during their interviews, we need to understand why finding an authentic career path feels so difficult in the first place.

Nathan identifies two structural problems that create widespread career confusion:

The Assembly Line Problem

Nathan: The education system, it's an assembly plant, right? It has to educate a massive number of people. And it has to do that in a consistent way. The way you systematize that is you put everybody in buckets. And especially in Europe, you're choosing a career path very early on, comparatively much earlier than you would be in the US. And I think that presents a real challenge because you're choosing a path as a young person with no experience.

This creates a fundamental mismatch: We're forced to make specific career decisions before we have any real understanding of what different types of work actually feel like.

Dive Deeper: Nathan and his team explore this assembly line problem extensively in Chapter 1 of their book "Roadmap: The Get-It-Together Guide For Figuring Out What To Do With Your Life."

One of my favorite quotes from this chapter:

“Most people who are successful . . . didn’t do what everybody else did. They didn’t go the same routes everybody else went. It is the people who think outside the box in whatever discipline they are in who shake the world. No one’s looking around at the people who followed a manual saying, ‘My God, they followed that manual in a way that was just inspiring.’ It is the people who throw the manual away and say there is something beyond this that I can share, or that I can give, or that I can invest, who become successful.” —JEFF JOHNSON, BET host and political activist

The Vulnerability Problem

Nathan: And then I think another big challenge is that there's not a lot of space for people to be vulnerable, especially in a public manner. If I go to speak at South by Southwest Conference, when I put my little bio together, it's not full of all of my failures and all the times that I've wandered. It's all the things that sound smart, right? New York Times bestselling author, great. That's what I'm going to put there.

This creates a devastating cycle:

People hide their uncertainty and struggles

Others see only the polished success stories

Everyone feels alone in their confusion

The myth of the "perfect path" perpetuates

85 Interviews, 18,000 Miles, Three Life-Changing Discoveries

Now, let's return to what Nathan and his friends discovered during their road trip—findings that would shatter everything they thought they knew about successful careers.

What Nathan and his friends expected to find: People with perfect, linear career paths who always knew what they wanted to do.

What they actually found: Something completely different—three revelations that would reshape their entire understanding of how careers actually work.

The First Revelation: Everyone Struggles (Even After "Making It")

Interview after interview revealed the same shocking pattern:

Nathan: Every one of these people felt similar to us. Whether they knew who they were at the start or whether they had to figure that out, they all had that sense of insecurity. Howard Schultz who started Starbucks—he was so poor in college that he was donating blood just to have enough money to eat. Michael Dell, when he started Dell computers—he dropped out of college, but he was so afraid to tell his parents that he dropped out of college that he just didn't, he avoided the conversation.

The idea that everybody had this perfect curated path was so not that. I don't know why we thought that. Maybe it's because if you look at everybody's LinkedIn profiles—everybody curates this perfect little path of "I did this, and then I did this, and then I did this." There's no space to celebrate "Oh, I was totally lost here." That's not rewarded in our society—to talk about fear and loss and wandering.

I don't think people get the message or hear it enough that we all struggle, that we all fail, that we're all experiencing some sense of doubt, that even when we've made it, we'll feel this imposter syndrome.

What Nathan discovered challenges everything we're told about successful people:

They didn't have it figured out early - Most were just as lost as everyone else

Their paths weren't linear - Full of twists, turns, and seeming dead ends

They started with curiosity, not certainty - Small interests led to big careers

They struggled with doubt too - Even after "making it," they felt imposter syndrome

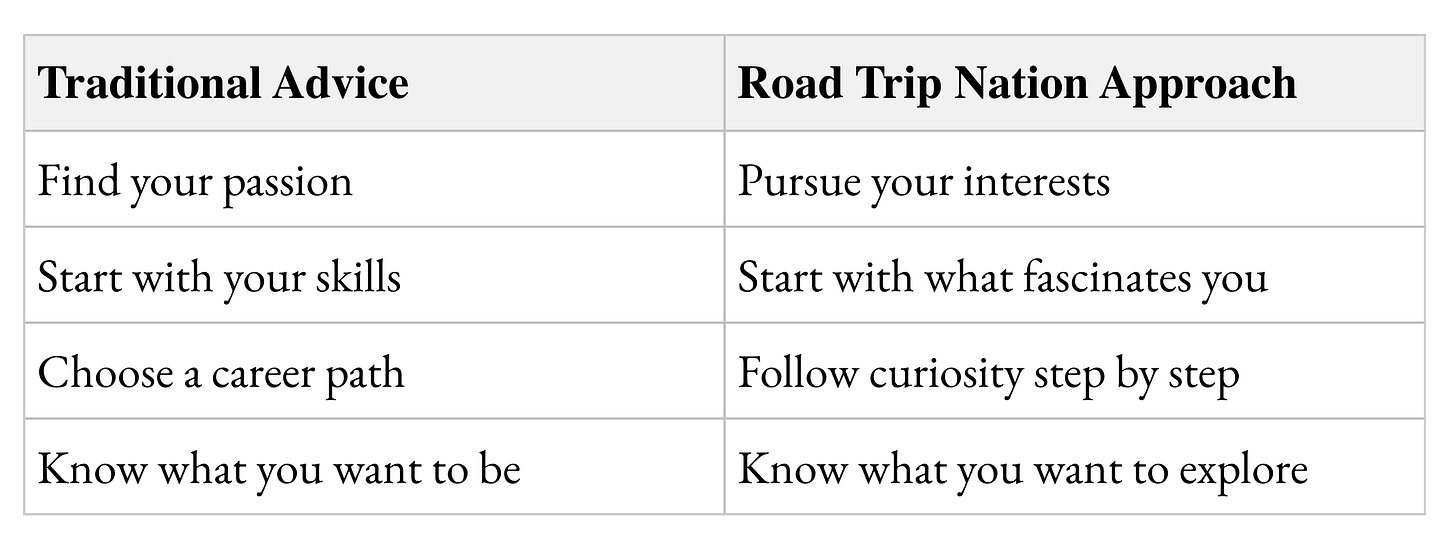

The Second Revelation: Follow Interest, Not Passion

The second breakthrough discovery was perhaps the most counterintuitive: the people they interviewed didn't follow their passion—they followed their interests, and passion developed along the way.

Nathan: We believe that there are as many paths to a fulfilling work life as there are people in this world. So it's not something that is exclusive to one group or the other. But I would say at the heart of it, in the most simple way, people that we interviewed, they pursue their interests.

Why "Follow Your Passion" Is Bad Advice

Nathan: I think a lot of people say start with your skills and then develop a career there. But I think that misses a few things. I think it's easy, especially when you're young, it's easy to look at a skill and mis-attune that into a direction that you're really not interested in. So I might be skilled with a spreadsheet, but that doesn't mean that's what gives me joy, right?

And it's not saying follow your passion because I think the "follow your passion" piece— there's a couple of things that are challenging with that. Number one is who knows what their passion is, especially when they're younger? Our point of view is that's a destination. You pursue your interests, you build a life around your interests, and ultimately you arrive at a place where you're passionate about the work that you do.

The Interest-First Approach

Nathan's approach flips conventional wisdom:

Nathan: Start with something that's interesting and then you'll have the commitment and the energy to develop skills around that. The surgeon that I want to operate on me when I break my clavicle is not the surgeon that went into it because it makes a lot of money. It's the surgeon that is fascinated by the human body and pursued that interest and then developed a skill set around that interest.

Dive Deeper: Chapter 9 of the Road Trip Nation book explores this interest-first philosophy in greater detail, offering practical exercises to help identify your genuine interests versus what you think you should be passionate about.

A quote I love from this chapter:

The Third Revelation: Foundation vs. Interests

The third and perhaps most practical discovery was understanding the difference between your "foundation" and your "interests"—a framework that can revolutionize how you approach career decisions.

The Foundation vs. Interest Framework

Nathan: Start with something that's interesting and then you'll have the commitment and the energy to develop skills around that. The surgeon that I want to operate on me when I break my clavicle is not the surgeon that went into it because it makes a lot of money. It's the surgeon that is fascinated by the human body and pursued that interest and then developed a skill set around that interest.

For Nathan, his foundation is "making things." But how he expresses that foundation has evolved dramatically over 20+ years:

Nathan: For like five or 10 years, that making stuff was editing. And then as we grew, directing our documentary series. But then ultimately, I had done 10 years of that and was ready to train people to take my place so that I could move into a different space. And so I went from editing to directing to then executive producing the series.

Then his interests expanded into product development, web-based tools, and multiple books. Now he describes himself as a "futurist" at Road Trip Nation, exploring how AI might redefine career exploration.

Breaking the Career Box Myth

Nathan: I think throughout my education, I always felt like there was this very singular path that you would have to choose like, "Oh, I'm going to study marketing, and then I'll be a marketing person." But what's absent of that is like, where do you do that marketing? Are you passionate about improving and changing the world? Well, marketing for a nonprofit. Do you do the environment? Marketing and social media for Greenpeace, right? But this idea that careers are these little tiny boxes that only make up one thing, it's just not true.

The Michael Jagger Revelation

Nathan's understanding of his foundation crystallized through an interview with Michael Jagger, creative director at Burton Snowboards:

Nathan: I knew I always liked making things, but I also wasn't that good. Like if I drew you a drawing, you would say it's pretty shit. Like my 12-year-old probably can draw a better horse than I can. And I love woodworking, but I wasn't going to be a master carpenter by any means.

I have very old memories of just pounding nails into wood for hours on end. And so in hindsight, I could look back and say I love making things, but I was out of touch enough that that was something to name or take seriously to the point that when I chose a major for college, I chose management, business management, which is just ridiculous. I'd never managed a thing in my life.

But I always had this feeling that I could look at something and get a sense of how it could be better. Like something that drives me nuts is when you walk into a building and the door has a sign that says "push." If that door was designed right, if the handle was designed right, if there was a clear affordance to that door, you wouldn't need a sign.

The Creative Director Breakthrough

Nathan: I always had this ability to observe things and think how could they be better? But I had no context of the word "design" and I had no context that that skill set was actually a job until we got to Burton Snowboards because Michael Jagger was a creative director.

And so he's a creative director. He's inspiring a team of skilled individuals—whether that's designers or engineers or front-end developers—to make something. But they're all more skilled than he is, but he has this larger vision that can see what it can be.

This was Nathan's lightbulb moment—realizing there was a career that would fit his unique makeup.

Dive Deeper: Chapter 9 of their book provides an excellent framework for defining your own foundation. The chapter includes practical exercises and thought-provoking questions to help you identify what truly drives you.

Here's a helpful excerpt I found particularly useful for defining my own foundation:

Success Stories: People Who Applied The Interest-First Approach

Let's look at real examples of people who found extraordinary careers by following their interests rather than conventional advice.

The Man Who Landed on Mars Without Knowing Stars Move

One of Nathan's favorite examples perfectly illustrates the interest-first approach—the story of Adam Steltzner, who became lead engineer on the Mars Curiosity rover landing system.

Nathan: He realized one day or one night going across the bridge that he went consistently, that each time he crossed that bridge on a different night, the stars were in a different place in the sky. In his own words, he's like, "I clearly was not paying attention in school." He just went one step with that question and said, "I'm going to go figure out why the stars move."

And it just all of a sudden, he was tuned into this interest that propelled him to go into college, get his master's, get into engineering. He ultimately ended up getting a job at Jet Propulsion Laboratory at NASA, and he is the lead engineer on the landing system for the Mars Curiosity rover. So somebody who landed a spaceship on another planet got their start when they didn't even know that stars moved in the sky.

His story perfectly illustrates the interest-first approach:

The progression was:

Curiosity: "Why do stars move?"

Small step: Took one class about astronomy

Growing interest: Got pulled deeper into the subject

Skill development: Developed engineering capabilities

Passion: Became passionate about space exploration

Expertise: Led the Mars rover landing team

KEY INSIGHT: Passion is often the result of pursuing interests, not the starting point.

YOUR TURN: What's one thing that genuinely interests you but that you've dismissed as "not practical" or "not a real career"? What small step could you take this week to explore it further?

From Shy Kid to MMA Success

Nathan: We interviewed this guy named Ariel Hawani, and he described—he said in high school, he was so shy and so afraid of being in public that he would hide in the bathroom when a lot of people were around. He would be conscious of when and how he would move around campus because he didn't want to run into too many people. But ultimately, he found mixed martial arts and loved it.

He found that even though he was shy, he was articulate when talking about something he was passionate about. He ultimately pursued that interest where many people would say, "MMA is a thing you do before or after work, but not the thing you do."

Ariel's story shows how interests can transform not just careers, but entire identities. What started as a personal interest in overcoming shyness became a professional pathway that leveraged his natural communication abilities within a field he truly loved.

The Nike Designer's Strategic Pivot

Nathan shares the story of Tinker Hatfield, head of design at Nike, to illustrate how career changes happen later in life:

Nathan: He was always interested in sports, but felt like sports was this thing you do on the side. It's a hobby. If you're not a professional, then you throw sports away, and then you have to grow up. And so out of college, his grow-up job was to become an architect.

But he realized that sports was such a part of his life that he couldn't let it go. His solution?

Nathan: He took that architecture job and just went a few degrees to the left and started doing architecture for Nike. And so he got a job doing their Nike stores and doing the design and architectural design for their stores, all the while expressing his interest both in Nike and sports and trying to get closer.

A Cautionary Tale: The Family Barbecue Trap

Nathan's own near-miss with a career he would have hated perfectly illustrates how social pressure can lead us astray. His story serves as a warning about the dangerous power of choosing careers based on what sounds impressive rather than what genuinely interests us.

Nathan: It is easier to follow a well-worn path, right? How many people unfortunately are doctors because it's the thing that is easy and comfortable to say when you're at the family barbecue? "Oh, what are you studying or what are you going to be?" "Oh, I'm going to be a doctor." The second you say doctor, everybody's like, "Nathan's got it. He's smart. He knows what he's doing." But what am I going to say? "I like making things. I don't know what I'm going to be." All that does is bring tension into that family barbecue.

So I think life is structured, going back to that lack of vulnerability in a way that we don't want to share that vulnerability. We'll follow the path that's in front of us, we'll do the thing that sounds the best. When I said I was going to be a management consultant at the family barbecue, all that "What are you going to do with your life?" went away because I had something smart that I could say and literally, Marco, I manifested that. I learned the little trick that if I said I'll do this career that sounds smart, everybody will think Nathan's smart.

And so then I just went to college to be a management consultant. And if I hadn't done road trip, I would be a very disgruntled—maybe even skilled because I do like managing, I love building a team and leading. So I probably could have done that reasonably well. And it would have been this whole, I talked my way into it. I manifested it backwards. I started out of sheepishness, and uncomfortability with not being able to say "I don't know what I'm doing." So I masked my fear, wrapped it in a career that I had actually no interest in but sounded good at the family barbecue.

This backward manifestation—choosing a career based on social approval rather than genuine interest—is tragically common and leads to decades of quiet dissatisfaction.

The Danger of Abandoning Interests Too Early

One of Nathan's most important insights comes from radio legend Ira Glass, whose story illustrates why many people give up on their true interests before developing the skills to succeed.

Nathan: I think a lot of people can articulate "Oh, this is interesting, but I'm not skilled at it." And I think that one of my favorite interviews which connects to this is a guy named Ira Glass.

Before podcasting was podcasting, he defined what radio and then podcasting became in many ways. And the thing that was so meaningful to me was he talked about the need to wade through the gap between this time where you know what you want to do, but you're not very good at it. And he talked about when he first edited radio and first did some radio pieces on NPR.

And actually, when we interviewed him, he was in the control room and he was able to pull up these very early interviews that he had. And he played some of them. And he's like, "There is no hint at all that I am any good." Literally, I think he had somebody say, "That's the worst piece I've ever heard of somebody trying to get on radio." And what he talked about was this chasm, this gap between that time when you don't have the skill, but you have the ear—he knew what good was, but he didn't have the skill to get there. And so many times we abandon that interest, because it doesn't feel right, because we haven't put in that time to get to the place where the skill feels right.

This "gap" between interest and competence is where most career dreams die. The key is persistence through the inevitable period of being "not very good yet" at something you find fascinating.

Breaking the Vulnerability Cycle

Nathan's advice for dealing with uncertainty:

Nathan: You got to take the pressure off of yourself for finding the thing. That's why we don't say find your passion—it's just pursue an interest and don't figure out the big thing. Figure out the next small step that gets you closer to a profession that is embodied in your interests.

When Road Trip Nation finished their documentary, they had 461 hours of footage but no idea how to edit:

Nathan: It would have been one thing to freak out and been like, "Oh, we got to hire a professional, somebody that knows what they're doing." But ultimately, I went to Barnes and Noble and got an instruction manual for Final Cut Pro, which was the editing software we were using at the time, and just started reading the manual on how to edit. Even before I had a computer and the software in front of me, I would go into the Apple store and figure out like, "Oh, that's what I was reading about."

KEY INSIGHT: Everyone is figuring it out as they go. The people who seem to have it all together are simply better at taking the next small step despite uncertainty.

From Project to Mission: Building Road Trip Nation

Here's where most stories would end: Three friends have an adventure, learn some lessons, graduate, get jobs. But Nathan's story was just beginning.

The hard part wasn't the road trip—it was what came after.

Nathan: We called it a project for years and years and years. There was no sign that this was going to become something. It was just a kind of instinctual feeling that myself and Mike and Brian all had, that it could become something.

The Five-Year Struggle

Building something meaningful takes time. Nathan's story illustrates just how much time:

Nathan: It was probably three or four years into, maybe even five years into Road Trip Nation that we took the word "project" off of our language and we would say, "I work at Road Trip Nation" as opposed to, "Oh, I'm doing this project called Road Trip Nation."

Five years. That's longer than most college degrees. Longer than most people will stick with anything uncertain.

How did they survive?

Nathan: I'd acknowledge the privilege that myself and my partners had, which is all three of our parents were willing to let us live at their home. And so we kept our expenses literally down to almost zero. If we went out—we never went out—but if we went out to like a Mexican restaurant, this is not an exaggeration, we would buy one beer and eat the chips and salsa. And that was like going out.

The Drip-by-Drip Philosophy

Nathan's grandmother had a saying that became their guiding principle: "A drip and a drip makes a splash."

Nathan: We finished the first road trip. And we worked our asses off to get press for that trip. And we got next to nothing. We got a few articles in a local paper. But we literally got like a section like that big in a Forbes magazine—maybe two paragraphs, a little blurb.

Then, somebody from Random House Books saw that article, contacted the author and said, "Hey, would they ever like to write a book?"

The author reached back to us and said, "Hey, this person's interested. I loved working with you guys. What do you think? Let's write this together." Her name was Joanne Gordon. And so from our first—coming back from the road, we were living with our parents. We invited this incredibly successful writer from Forbes magazine to come to California for two weeks and live at my parents' house. And we wrote this book together. And the signing bonus of that book was just enough to pay our debts back.

And then we started editing all the footage because we filmed everything on the trip. And right at the time we were starting to edit that, one of the people that we interviewed from Nike called and said, "Hey, I was just thinking about you guys. How are you?"

Literally just a check-in. And we had told him, "Hey, we're writing this book and we're making this film and we'd love to share this film." And he was like, "I think I could get Nike to help out." And so he ended up giving us a little bit of money to finish the film and then take it on tour.

A drip and a drip makes a splash. Each small win created the next opportunity.

Nathan: Between the check from Random House and the check from Nike, we had just enough to do the tour and finish the film. And then we came back with, I think we had $5,000 in our bank.

The $5,000 Validation

With their last $5,000, they made a crucial decision that would validate their entire approach:

Nathan: We took that last $5,000 and we ripped out the back—there used to be a bathroom back there in the RV—and we ripped that out so that we could fit five people in this RV. And we put an application out to college campuses to see if anybody else would want to replicate our experience. "We'll film it, we'll give you the keys, we'll pay for the trip, but you have to do your interviews. You find people you're interested in, you basically in your own way replicate the trip."

We ended up finding an incredible team and so with our last $5,000, we filmed a three-week road trip with these three guys from Brooklyn. They had the same meaningful experiences we did. And so that was this validation mark, another drip.

REFLECTION: What project or interest have you abandoned too early? What if you gave it the five-year treatment instead of the five-month treatment?

Success Redefined

After 22 years of interviewing people who love their work, Nathan has developed a nuanced definition of success that challenges conventional metrics.

Nathan: At the highest level, I would say my definition of success is to be happy. And happy isn't void of struggle and challenge. But ultimately, do I feel like my time is well spent? Do I feel like I'm supporting those around me?

But that happiness, it shifts, right? Like when I was 20-something, it was all about me. But right now I'm a father of three daughters. And so my happiness is very intertwined with making sure I can be the best husband to my wife and the best parent to my kids while also being deeply invested in Road Trip Nation.

And so that makeup shifts and evolves over time. And I guess that's that other part, right? You don't ultimately find that perfect career and you don't ultimately find that perfect definition of success and then everything's static from there. The only constant is change. And it's kind of hard to accept that change is the only constant.

The Career Evolution Reality

Nathan points out something crucial about the modern economy:

Nathan: Just look around you right now and think—if you were to write a hundred careers that are compelling and interesting to you right now, I would bet you that 60% of those careers didn't exist 15 years ago.

This means:

The career you're "supposed" to prepare for might not exist when you graduate

The career that's perfect for you might not exist yet

Adaptability matters more than certainty

Your definition of success will inevitably evolve

Success Metrics That Actually Matter

Based on thousands of interviews, Nathan suggests success isn't about:

Job titles or prestige

Salary or material accumulation

Following a predetermined path

Avoiding uncertainty or struggle

It's about:

Feeling energized by your daily work

Supporting the people you care about

Contributing something meaningful

Continuing to grow and evolve

Staying true to your interests and values

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: The Road Trip Nation Philosophy.

After diving deep into Nathan's 22-year journey, several powerful principles emerge that can guide anyone seeking a more authentic career path:

The Core Principles

Start with interests, not passions - Passion often develops after you pursue what genuinely interests you

Take the next small step - Don't try to figure out the entire path; just focus on the next logical move

Embrace being lost - Uncertainty isn't a bug in the system; it's a feature of authentic exploration

Build bridges, not walls - Career changes work better as incremental shifts than dramatic pivots

Separate foundation from interests - Know your core way of being, but let your interests evolve

Question the "well-worn path" - The easy answers often lead to lives we never actually chose

Share your uncertainty - Vulnerability creates connection and breaks the myth of the perfect path.

The Three Questions That Change Everything

Based on Nathan's experience, here are the questions that matter most:

"What genuinely interests me right now?" (Not "What should I be passionate about?")

"Who can I talk to who loves work similar to what interests me?" (Not "What does the internet say about this career?")

"What's the smallest step I can take to explore this further?" (Not "What's my five-year plan?")